Comprehensive Guide to Computer Virus Protection

Why Computer Viruses Matter: Context, Stakes, and the Roadmap

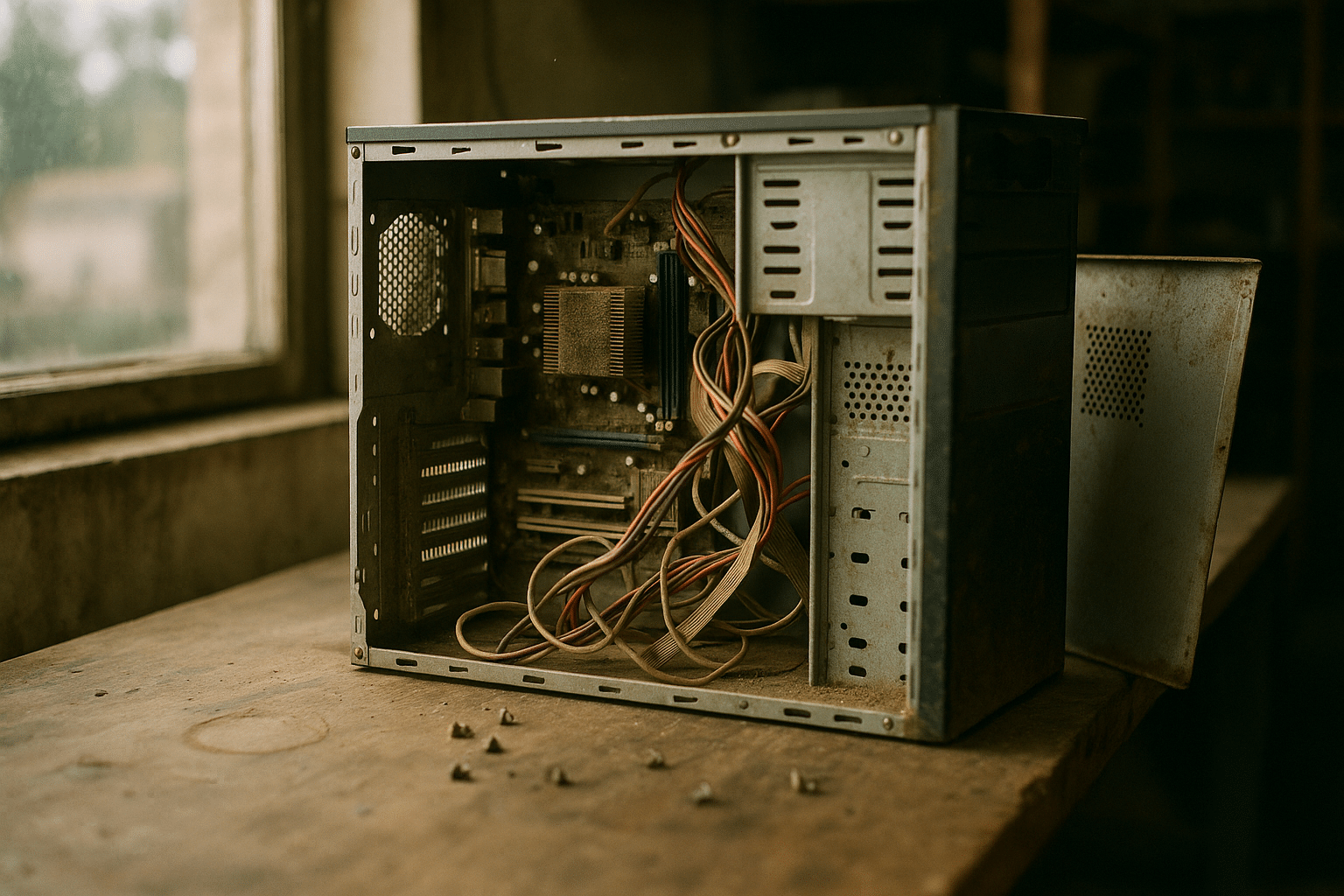

Computer viruses are tiny programs with outsize consequences, engineered to replicate and spread by attaching to legitimate files or processes. They matter because they convert everyday actions—opening a document, plugging in a removable drive, clicking a link—into potential gateways for disruption. For households, that disruption can mean corrupted files or stolen passwords. For organizations, it can ripple into downtime, reputational damage, and costly recovery. The good news is that a clear understanding of what viruses are, how they differ from other threats, and how to build layered defenses dramatically lowers your risk.

Outline for this guide:

– Definitions and distinctions: virus vs. other malware

– Infection vectors and lifecycles: how viruses get in and persist

– Types of viruses with real-world comparisons and examples

– Layered protection across people, process, and technology

– Response and recovery: a calm, repeatable playbook

Why this roadmap matters now: the attack surface has expanded. More devices, more cloud accounts, and more software dependencies mean more places for a virus to hide. Email remains a frequent entry point for malware-laden attachments and links, while document macros and installer scripts continue to be abused for initial footholds. Removable media still plays a role in closed or semi-isolated environments, and shared network storage can amplify a single mistake into a teamwide problem. High-profile outbreaks have shown that even decades-old techniques—such as tricking users into running code—still work because they target our habits and time pressures.

This guide aims to translate security concepts into practical steps you can apply today. It avoids hype and focuses on actions that reliably reduce risk: maintaining current software, limiting privileges, validating the file origins you trust, and practicing rapid containment if something slips through. Along the way, you will find comparisons between major virus categories and concise checklists that turn abstract advice into routines. By the end, you will have a plan that respects your time while improving resilience for both personal devices and small teams.

How Computer Viruses Work: Entry Points, Replication, and Stealth

Viruses share three essential traits: a delivery method, a trigger to execute, and a replication routine. Delivery is commonly achieved through user-initiated actions such as opening attachments, enabling macros, running installers, or interacting with removable media. Once executed, a virus attempts to attach to files, processes, or system areas so it can spread further, either on the same device or to others. Many modern strains also include a communication component, reaching out to remote servers for updates or additional payloads, though classic viruses may operate without network access.

Common infection vectors include:

– Email attachments disguised as invoices, resumes, or urgent notices

– Documents that request enabling macros or content to “view properly”

– Installer packages bundled with unauthorized add-ons

– Removable drives that contain hidden or autorun-style files

– Compromised websites that deliver drive-by downloads through outdated software

Replication strategies vary by target. File-infecting viruses append or insert code into executable files so each run propagates the infection. Macro viruses piggyback on document templates, spreading when files are opened and saved across shared drives. Boot-sector infections attempt to load before the operating environment, giving them persistence even if certain files are cleaned. Network-aware strains seek writable shares to copy themselves broadly, exploiting predictable folder structures and permissive access controls. Some viruses add stealth tactics such as obfuscation, polymorphism (changing code signatures with each copy), or process injection to evade simple detection.

Why defenses fail often comes down to predictable behaviors. People are inclined to trust known senders or familiar formats, systems are sometimes behind on updates, and default settings may allow risky actions like automatic macro execution in certain contexts. Attackers rely on this frictionless path. Mitigation therefore pairs technical controls with habit-shaping: harden settings to block known abuse paths, keep software current to deny exploitation, and coach users to pause before opening surprising files. Historically, large outbreaks leveraged old vulnerabilities or social engineering rather than novel genius, demonstrating that steady hygiene outperforms exotic countermeasures.

Types of Computer Viruses: Distinctions, Comparisons, and Real-World Patterns

The term “virus” is sometimes used broadly, but precision helps. A computer virus is malware that replicates by inserting itself into other files or system areas. In contrast, a worm self-propagates across networks without attaching to a host file, and a trojan disguises itself as legitimate software to get installed. Many real-world campaigns blend techniques: a trojanized document may deliver a file-infecting component, or a worm-like routine may help a virus traverse shared storage. Knowing the primary mechanism matters because it suggests the most effective controls to apply.

Notable categories include:

– File-infecting viruses: attach to executables, triggering replication when the file runs

– Macro viruses: leverage scripting inside office documents and templates

– Boot-sector viruses: target early-loading areas for persistence

– Polymorphic or metamorphic viruses: alter their code to evade signature-based detection

– Network-aware viruses: spread via shared folders and weak permissions, approaching worm-like behavior

Comparing behaviors clarifies risk. File infectors can silently corrupt frequently used programs, leading to gradual spread and integrity loss. Macro viruses excel in collaborative environments, where documents circulate rapidly among teams. Boot-sector infections are less common today but remain impactful where removable media is prevalent or where legacy systems persist. Polymorphic variants complicate straightforward signature detection, pressing defenders to combine behavior-based analytics with traditional scanning. Network-aware strains turn a single misconfigured share into a springboard, making access control and segmentation crucial.

Historical examples illustrate patterns without needing sensationalism. Email-borne outbreaks at the turn of the century showed how curiosity and urgent wording prompt clicks, while later waves demonstrated that document scripting remains potent whenever macros are loosely controlled. Campaigns have caused widespread downtime, with damages often tallied in lost productivity rather than dramatic headlines. The practical takeaway is consistent: recognize which channels are active in your environment—documents, installers, shares, or removable media—and harden them. By aligning defenses to the virus type most likely to appear, you reduce both infection probability and clean-up effort.

Layered Protection: Practical Habits and Controls That Hold Up

Effective protection is a system, not a single tool. The goal is to make each step an attacker relies on—delivery, execution, persistence, and spread—less likely to succeed. Start by keeping software current. Timely updates for the operating environment, browsers, document viewers, and runtime components close off the older vulnerabilities that many campaigns still target. Combine this with conservative settings: disable or limit risky features like macros by default, block auto-run behaviors on removable media, and require user prompts for script execution in everyday contexts.

Build layers you can maintain:

– Patch routinely, prioritizing publicly exploited vulnerabilities

– Limit administrator privileges to only what tasks require

– Use application allowlisting or reputation-based controls for new binaries and scripts

– Scan downloads and attachments before opening, ideally in a separate, restricted context

– Segment networks and tighten access to shared folders, especially those used for templates or installers

– Back up critical data following a 3-2-1 approach: three copies, on two media types, with one offsite or offline

Human factors matter as much as settings. Encourage brief verification rituals, such as calling a sender before opening a surprising attachment or using a separate channel to confirm urgent requests. Teach the habit of hovering over links to preview destinations, and normalize reporting suspicious messages without blame. Small teams can schedule 15-minute monthly check-ins to review updates, backup status, and any near-misses. These routines catch issues early and build confidence in the process.

On the technology side, pair signature-based scanning with behavior monitoring that flags unusual activity, like mass file modifications or unexpected process injection. Consider isolating high-risk work—testing downloads or opening unfamiliar documents—inside a disposable environment. Enforce least-privilege so that, if a virus executes, it cannot write to sensitive locations or propagate easily. None of these steps guarantees immunity, but together they raise the cost of attack and shorten the path to containment. The measure of success is fewer incidents and faster, cleaner recoveries when incidents occur.

Responding and Recovering: A Calm Playbook and Closing Guidance

Even strong defenses cannot eliminate all risk, so a measured response plan keeps setbacks small. The first step is containment. If a device shows signs of infection—unusual file changes, blocked security tools, or unexpected network activity—disconnect it from networks to prevent spread. Avoid immediately powering off unless necessary to stop ongoing damage; preservation can help with forensics. Document what you observed, including prompts, filenames, and timestamps, as this speeds analysis and reduces repeated mistakes.

A practical playbook looks like this:

– Isolate affected systems from networks and shared storage

– Preserve evidence: note alerts, keep suspicious files for offline analysis if safe to do so

– Run trusted scans from clean media, preferably offline

– Restore from known-good backups after verifying they are uninfected

– Rotate credentials that were used on the device and recheck multi-factor settings

– Monitor for recurrence with heightened logging for at least two weeks

Recovery is about confidence and integrity. Validate that restored files open cleanly and that routine tasks do not trigger new alerts. Review why the infection succeeded: was a macro policy too permissive, were patches stale, or did a shared folder have wider write access than intended? Address those gaps immediately. For teams, communicate clearly with stakeholders about impact and remediation steps, focusing on transparency rather than blame. Reporting significant incidents to relevant parties—such as partners who may have received infected documents—reduces downstream harm and builds trust.

Conclusion for everyday users and small teams: aim for steady, sustainable security. Keep software current, use conservative defaults, practice simple verification habits, and maintain backups you have actually tested. These actions cut through noise and deliver tangible risk reduction without requiring advanced expertise. If an incident occurs, act promptly, follow the playbook, and treat it as a chance to strengthen the system. Security is a practice, not a finish line; with consistent routines, viruses become manageable setbacks rather than crises.